June 2022: three fiction pieces by the great German-Jewish writer appear in English for the first time

Three Prose Works

by Else Lasker-Schüler

Rixdorf Editions is very proud to announce a major forthcoming anthology by one of the greatest German writers of the 20th century. Appearing in June 2022, Three Prose Works unites an interconnected trio of fiction publications by Else Lasker-Schüler originally issued before the First World War and presented here in English for the first time. The translator is James J. Conway who also provides an insightful afterword. Three Prose Works shows a vital facet of the German-Jewish writer’s creative output developing in parallel with her better-known verse, as she mythologises her own ceaseless quest for freedom and meaning in captivatingly original prose. Each of the three works is self-contained although they contain numerous thematic links with each other:

The Peter Hille Book (1906), is a collection of gem-like, Nietzschean tales in which her alter-ego ‘Tino’ shares the odyssey and the wisdom of ‘Petrus’, a stand-in for her beloved mentor Peter Hille.

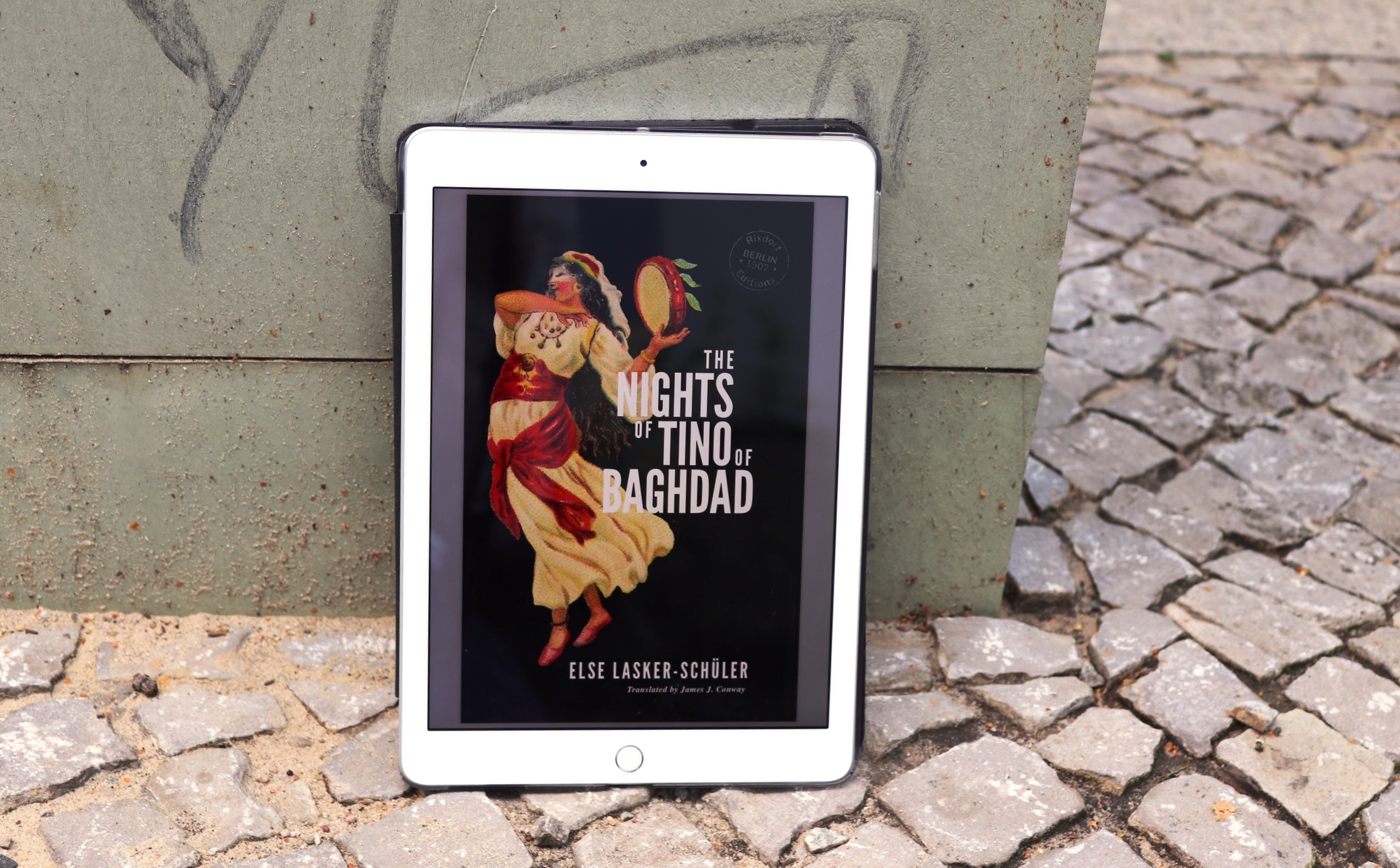

The Nights of Tino of Baghdad* (1907) is an episodic fantasia which explores a notional ‘Orient’ of the author’s devising, blending Muslim and Jewish traditions to explore the commonalities of Semitic identity.

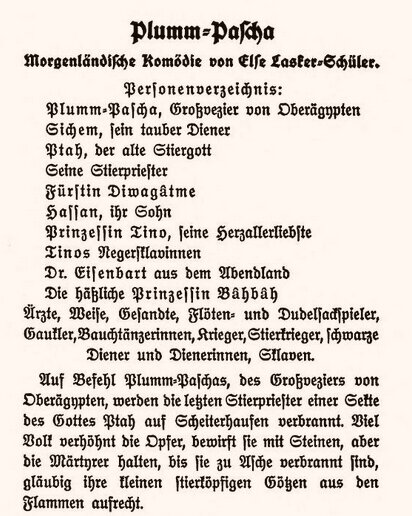

The Prince of Thebes (1914), issued on the eve of the First World War, offers a sequence of dark fables seething with violence and eroticism, culminating in a great clash of civilisations.

Cover artwork for Three Prose Works designed by Svenja Prigge

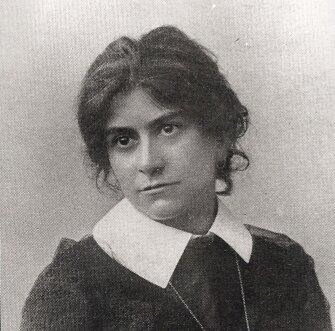

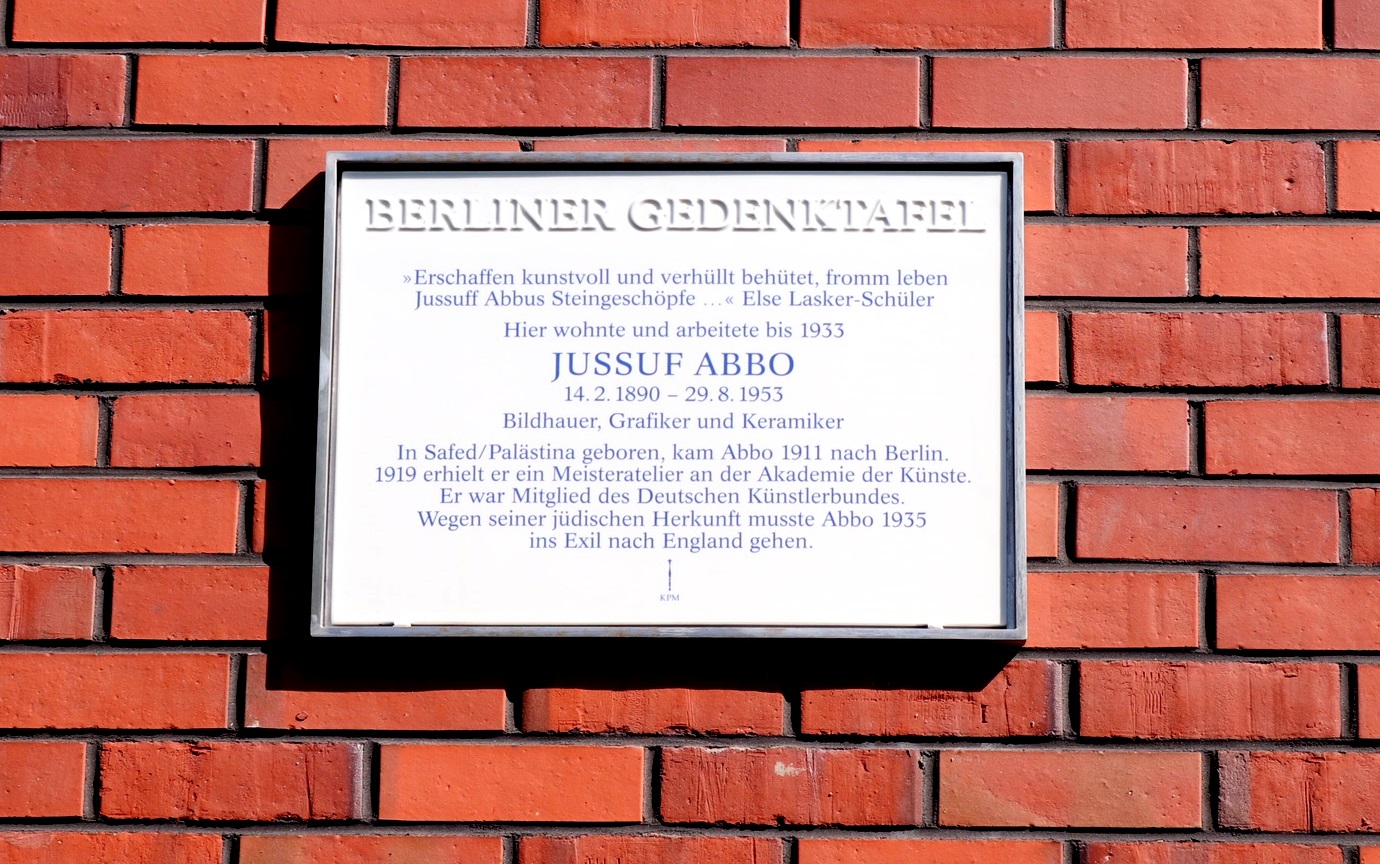

Else Lasker-Schüler (1869-1945) was a major voice of Expressionism and a bohemian fixture of early 20th century Berlin. She received Germany’s most prestigious literary prize shortly before she was forced into exile with the rise of the Nazis in 1933. While her verse works such as the late collection My Blue Piano continue to gain new devotees in English translation, her compelling, heavily autobiographical prose works largely remain to be discovered.

Described by the TLS as an ‘exciting new list’, Berlin-based Rixdorf Editions is introducing forgotten German classics to a contemporary English-language readership, focusing on the Wilhelmine period (1890-1918), when daringly innovative writers defied a reactionary mainstream. In bringing vital German texts from around the beginning of the 20th century to new readers, Rixdorf Editions has been particularly focussed on women’s writing; Three Prose Works is the eighth print publication by the press, half of which are by women. The Rixdorf list of original translations includes titles by Anna Croissant-Rust, August Endell, Franziska zu Reventlow, Hermann Bahr and Ilse Frapan, plus its latest work, Papa Hamlet, by Arno Holz & Johannes Schlaf (October 2021), and its best-selling title, Berlin’s Third Sex by Magnus Hirschfeld (2017). Three Prose Works is the last in this current series of rediscovered German literary treasures from Rixdorf Editions, which will return with a new format in late 2022.

* subscribers to the Rixdorf Editions mailing list had a preview of The Nights of Tino of Baghdad, which was issued in electronic form in 2019 and since deleted.