Antisemitism by Hermann Bahr (translation by James J. Conway) has been reissued by the University of Toronto Press (June 2025).

The information below relates to the original Rixdorf Editions publication of this book in 2019.

‘Antisemitism is the creed of the scoundrel. It is like a ghastly epidemic – it can neither be explained nor cured.’

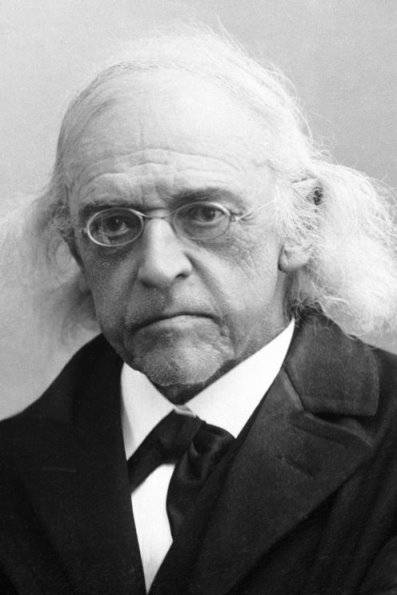

Hermann Bahr

Antisemitism

Translated by James J. Conway

Design by Svenja Prigge

21 October 2019

244 pages, trade paperback

115 x 178 mm, French flaps

ISBN: 978-3-947325-10-8

Deleted

In 1883, Austrian author Hermann Bahr was arrested for antisemitic abuse. Ten years later, he was a champion of the Viennese avant-garde and its numerous Jewish exponents, and would soon marry a Jewish actress. In Antisemitism Bahr makes the political personal (and vice versa) using the then-novel form of the interview for a sweeping international survey of the most contentious issue of his day. His respondents are economists and anarchists, preachers and political grandees from across Europe, with such figures as activist Annie Besant, novelist Alphonse Daudet, polymath Ernst Haeckel and trailblazing socialist August Bebel. Now available in English for the first time, this hugely important document was originally published in 1894, and it captures the moment when an ancient enmity assumed new force, the age of the Dreyfus Affair and Germany’s pre-Nazi peak in politicised race hate. Antisemitism is no echo chamber, with some respondents offering robust defence of prejudices that would have harrowing consequences in the 20th century. But with its conspiracy theories, babbling demagogues and demonised minorities, Bahr’s investigation is sadly all too relevant today.

DOWNLOAD free PREVIEW (PDF)

Born in Linz, Hermann Bahr (1863-1934) was a vital catalyst for new writing across Europe. In the closing 19th century he marked out a route beyond Naturalism and is credited as the first proponent of ‘modernism’ as a literary virtue. As a novelist, journalist, essayist, critic and director, Bahr cultivated an extensive international network and was a pivotal figure in the ‘Young Vienna’ group which also included Arthur Schnitzler, Stefan Zweig and Karl Kraus. Leaving the reactionary views of his student years behind, he championed a cosmopolitan ethos exemplified by his belief in a ‘United States of Europe’. Common to each stage of Bahr’s cultural development were fearless rhetoric, intellectual curiosity and an unfailing sense for the next literary breakthrough. A handful of his critical and dramatic works appeared in English in the early 20th century.

related

Q&A with translator James J. Conway (PDF)

Background notes (PDF)

Now reissued by Rixdorf Editions, it is an important text from the high point of late 19th-century antisemitism, using interviews with key figures of the time to explore a newly relevant issue dividing European writers and intellectuals. […] a fascinating historical text …

— David Herman, The Jewish Chronicle

Originally published in 1894, it follows the author's candid exploration of anti-Jewish feelings as he sets himself to interview his most famous contemporaries on the topic (from August Bebel to Henrik Ibsen). The book's parallels with the present day – particularly early forms of populist politics and division as an electoral strategy – are unsettling and come as a sad reminder of how banal and deep-rooted our prejudices are: nihil novi, nothing new (or better) under the sun, no matter how far we think we might have progressed!

— Sarah Ollivier, Rene Blixer, Exberliner

… an extraordinary mea culpa by a former bigot turned anti-anti-Semite and defender of the Berlin avant-garde …

— Martin Billheimer, Counterpunch

It is to the translator’s credit that the book maintains such a high degree of readability while still sounding like something written more than 125 years ago. […] He masters the effect of the German while injecting the English with enough verve to keep it from bogging down into a syntactical morass. His stylistic choices become another critical buttress, much like the helpful notes, concise biographical sketches, and meticulous and accessible Afterword he provides, that serves the text well in its new life in English.

— Frank Garrett, My Crash Course

The vast majority of respondents condemn antisemitism but their answers are illuminating about the attitudes of fin de siècle Europe not only toward the Jews but also concerning nationalism, capitalism, sexism, and other issues that defined the era and much of the history that has followed it. Bravo for another illuminating Rixdorf edition!

— Bill Wallace

FROM THE AFTERWORD

In an age of widespread financial speculation and rapidly acquired fortunes, there was equally widespread suspicion of wealth gained not through labour or inheritance but investment, a phenomenon associated in the public imagination with Jews in particular. The ‘blood-sucking’ Jew of medieval legend – the avaricious money-lender, but also the parasite literally killing Christians for ritual purposes in the most extreme anti-Jewish legends – had now turned his attention to capital markets and would, the theory went, bleed them and their host nations dry. These notions were freely aligned with a wide variety of other political ideas of the time in ways that can surprise the present-day reader; anti-Jewish feeling was by no means confined to the reactionary right wing.

This brings us to a crucial point that helps explain why antisemitism could attain such heinous intensity – it was an extremely adaptable prejudice that could assume religious, racial, social, economic, political or cultural dimensions as required. Like a grappling hook, its strength and tenacity increased exponentially when two or more prongs were activated simultaneously. For the beneficiaries of declining economic structures, Jewry could be fashioned to represent the new power of capital, but the ethnicity of figures like Karl Marx and Ferdinand Lassalle also meant that socialism could be characterised as a Jewish conspiracy. Jews could subvert from above or below, as the covert string-pullers of international finance or as bedraggled immigrants from distant shtetls, competing in the market for low-paid labour. An early 20th-century German postcard neatly illustrates this duality in paired caricatures, with a Jewish hawker in ringlets selling coin purses alongside a big-nosed, cigar-smoking plutocrat counting his piles of gold coins.

In this edition

Antisemitism (39 interviews, plus the author’s introduction and conclusion, originally published as a series of newspaper articles entitled Der Antisemitismus for the Deutsche Zeitung in 1893; first book publication 1894)

Notes to the main text

Short profiles of the interviewees

Afterword by the translator, James J. Conway

Erratum

From p. 224 of the print edition of Antisemitism by Hermann Bahr (tr. James J. Conway):

… in 1886, Friedrich Nietzsche famously broke with Richard Wagner because of the latter’s extreme antisemitic views.

Naturally Richard Wagner’s death in 1883 (see p. 226) renders this scenario impossible. It was in late 1876 that Friedrich Nietzsche last encountered Wagner in person, his subsequent disenchantment with the composer having a number of causes, with antisemitism certainly prominent among them. It was some time after Wagner’s death that Nietzsche definitively, publicly rejected his influence, a break most clearly signalled in the book Der Fall Wagner (1888) and essay ‘Nietzsche contra Wagner’ (1889), written shortly before the philosopher’s mental incapacitation. This error in the Afterword has been corrected in the PDF sent out for review purposes.