August is Women in Translation month (take a look at #WITMonth on Twitter), and we are marking it with Else Lasker-Schüler’s contribution to a visionary pre-World War One cinematic/literary project, here in English for the first time.

Wilhelmine Germany was the birthplace of cinema, in the sense of a place where audiences pay to watch moving images. The year was 1895, the venue was Berlin’s Wintergarten – a variety theatre. This setting seemed to define the status of the new form; soon, short and artistically undemanding films were a common attraction in sideshows. Almost ten years later, there were hundreds of small neighbourhood cinemas throughout the country calling themselves ‘Kientopp’ or ‘Lichtspiel’ (literally light play), often playing imported films. The new art form still hadn’t entirely shaken its novelty status, but a small minority of creators and critics were beginning to see the phenomenal potential in film. In 1913, Else Lasker-Schüler was one of a number of avant-garde writers who took part in a visionary project which embraced cinema at a critical moment in its artistic and technical development. They believed that given sufficient scope, films might properly aspire to the status accorded to novels or paintings. The result was Das Kinobuch (The Cinema Book).

The project was conceived by Kurt Pinthus, a Leipzig theatre critic who at the time felt increasingly drawn to film. He knew there could be so much more to the medium than brief knock-about skits or even the more serious productions of the day which nonetheless treated cinema as theatre with a camera in front of it. For the Kinobuch he turned to writer friends such as Walter Hasenclever, Franz Blei and Paul Zech, all of whom were associated with Expressionism. While Germany’s dominant avant-garde strain had been gathering force for about a decade, it was only in 1911 that it was baptised by its greatest critical champion, Herwarth Walden, who at the time was still married to Else Lasker-Schüler.

Pinthus got each of the writers to submit an original film concept in the form of a script or treatment (although with no dialogue, early screenplays were treatments, more or less; the script for Georges Méliès’s revolutionary Trip to the Moon, for example, was essentially 30 bullet points). While the contributors may all have issued from the same milieu, their responses to Pinthus’s challenge could not have been more varied. Max Brod conceived a journey into the rich imagination of a bookish twelve-year-old, the camera following him through the day and showing us what he could only see in his mind. Albert Ehrenstein contributed one of the most elaborate scenarios, a variation on Homer and the Odyssey. Elsa Asenijeff delivered an extensive narrative that offered little of her usual formal daring, but in its centring of emotion and female experience, it reads almost like the précis of a great, lost Douglas Sirk melodrama; one dramatic turning point is even triggered by a car accident (try pulling that together on stage). Franz Blei simply submitted a letter explaining why he didn’t want to take part; “plays without words are pantomimes,” he complained, and “filmed pantomimes are weak surrogates.” Instead he advocated for a cinema that documents human lives, thus accidentally inventing reality TV.

All of these writers were associates of Else Lasker-Schüler. Even Ludwig Kainer, the artist who provided the cover, was a friend; in her epistolary novel My Heart she describes a plan for him to illustrate her ‘caliph’ stories (presumably a reference to the Orientalist tales that made up The Nights of Tino of Baghdad). Kainer contributed to the satirical journal Simplicissimus but around the start of the First World War, perhaps inspired by this book, he began working on film set design. He also designed posters for Valeska Gert, arguably the most radical performer of Weimar Berlin.

The timing of Das Kinobuch was propitious. Although officially dated 1914, its actual arrival in 1913 came at a turning point for German cinema, as though in simply issuing the book the vision of an artistically ambitious cinema was made manifest. This was the year of Carl Froelich’s Richard Wagner, the first biopic and perhaps the first feature film as we know it today, with its unprecedented run time of 80 minutes. It was also the year of The Student of Prague by Hanns Heinz Ewers, considered both the first auteur film and the first horror film. Its daring use of double exposure and other new techniques, feats that were impossible to replicate on stage, were precisely the kind of innovation to which the writers of Das Kinobuch aspired. Considering that Expressionism would be the dominant mode during Germany’s explosion in cinematic brilliance after the First World War, Das Kinobuch can be seen as something of a game plan, a statement of artistic intent, a vision of filmic excellence projected far into the future.

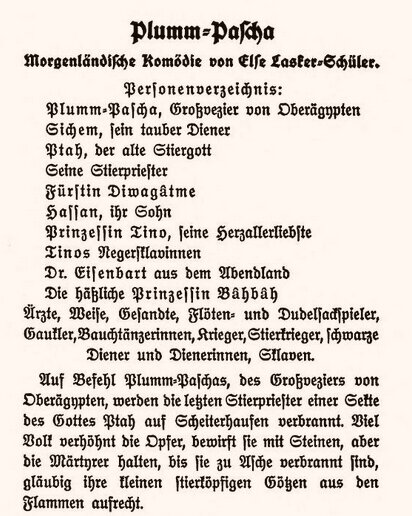

Else Lasker-Schüler’s contribution to Das Kinobuch was ‘Plumm Pasha’, which is also the title of one of the short tales in The Nights of Tino of Baghdad, although the treatment is not an adaptation. Rather, it incorporates the title character and other figures from the book – including Hassan, Diwagâtme and Tino herself – into a stand-alone scenario. ‘Plumm’, incidentally, means ‘plum’, but not in standard German (where it is ‘Pflaume’) but rather the Plattdeutsch dialect of the writer’s childhood.

The first edition of Tino had appeared six years previously, in 1907 (with the second six years in the future), and Lasker-Schüler was still very much dwelling in the world she had created. But here we witness a fascinating stylistic transformation; the narrative is just as absurd, the characters no less singular, but here their exploits are rendered in a clipped, utilitarian style, a bracing distillate of the heady, evocative prose of Tino.

In ‘Plumm Pasha’, Lasker-Schüler collapses dynastic and Ottoman Egypt into one plane. The clearest influence, apart from her own tales, is Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream – the confusion between dream and reality, the happy young lovers, the transformed head (here a bull rather than a donkey). The treatment follows comedic convention by concluding with a wedding, with farcical mix-ups, boisterous slapstick and even an extreme makeover along the way. But like The Nights of Tino of Baghdad, the narrative switches abruptly between tenderness, humour and violence; it’s hard to imagine any other comedy screenwriter opening with a burning at the stake. In every medium in which she operated – poetry, prose, graphics, drama, film – Else Lasker-Schüler was unmistakably herself.

Else Lasker-Schüler

Plumm Pasha

translated by James J. Conway

Characters:

Plumm Pasha, Grand Vizier of Upper Egypt

Shechem, his deaf servant

Ptah, the old bull god

His bull priests

Princess Diwagâtme

Hassan, their son

Princess Tino, his sweetheart

Tino’s black slaves

Dr Eisenbart from the West

The ugly princess Bâhbâh

Doctors, wise men, envoys, flute and bagpipe players, jugglers, belly dancers, warriors, bull warriors, black servants, slaves.

* * *

On the orders of Plumm Pasha, the Grand Vizier of Upper Egypt, the last bull priests of a sect of the god Ptah are burned at the stake. A crowd mocks the victims, casting stones at them, but the martyrs faithfully hold their little bull-headed idols aloft from the flames until they are burned to ashes.

Plumm Pasha emerges from his imperial palace, accompanied by his entourage, envoys in fezes and long, solemn robes. The Grand Vizier descends from his litter. It grows dark, lightning flashes, and suddenly the god Ptah is standing before Plumm Pasha; he curses the Grand Vizier and replaces his head with an outsized bull’s head (the turban remains unchanged and looks comically small compared to his bull’s head). Frightful bull-faced creatures dance around the hexed Plumm Pasha until the dawn breaks; Ptah has disappeared. The envoys have fled, the black servants drop the imperial edicts, and great confusion ensues. Only the deaf servant maintains his composure, bearing the startled Grand Vizier on a cushion of moss on which he sits cross-legged. Wise men come with instruments, microscopes, and large skull-measuring devices, but their counsel is without success; they begin to quarrel, tear at their beards and gesticulate violently with all their limbs. Slowly recovering, Plumm Pasha yells at his deaf servant, who takes a giant ear trumpet from a case that he carries with him and puts it on. Now he understands that his master is plagued by hunger. And he runs off to bring his master a cart full of hay to eat. Meanwhile the wise men advise him to summon Diwagâtme, the wise calipha of the city.

In the rose garden, the wise men encounter Hassan and Tino, sitting on a branch and hugging amidst the roses. Diwagâtme, Hassan’s mother, approaches them. The two lovers ask for her blessing, but she refuses it; she is miserly and tips her large bag up to indicate that she has no money left to build them a palace.

The wise men hear this and tell the trio about the fate of Plumm Pasha, and they are astonished. Diwagâtme explains that only the kiss of a pure woman can lift the Grand Vizier’s curse. She slyly turns to Princess Tino and tries to spur her to action; she would no longer be a poor princess because the Grand Vizier would shower her with gold and precious stones, and nothing would stand in the way of her marrying her son. Diwagâtme accompanies the wise men out of the garden. Tino’s playmates approach and dance a veil dance around the pair.

The Grand Vizier lies on the roof, roaring; suddenly a balloon appears with ‘Occident’ written on it. Dr Eisenbart climbs out of the balloon onto the roof, followed by living bottles with the inscription ‘Cow Lymph’. The servants want to prevent the inquisitive doctor from examining the angry Pasha. But they do not manage to prevent Dr Eisenbart from extracting lymph from the bull, until the Grand Vizier bites off his head; it is impaled on a long pole as a warning. Meanwhile the wise men approach and relay Diwagâtme’s wise words. The Vizier utters a roar of joy, stumbles a few times over the carpet on his roof and the wise men with him. Black boys cry out in the streets and market squares for a pure woman who might redeem the Grand Vizier for gold and precious stones. They write this on great banners that they carry around.

The Grand Vizier, surrounded by his entourage, rushes to the market square. Ten bulls with ten princesses approach; when they see the Grand Vizier roar they flee. Only one of them is prepared to kiss the hexed overlord of the city. Her veil is removed; but she is so hideously ugly that the Grand Vizier resolutely refuses her kiss. She is tall and skinny. Barbers come with large hedge clippers and trim her hair. Buckets full of make-up are brought in and the princess is made up, her lips and cheeks coloured with large paintbrushes. But Plumm Pasha waves dismissively, despite the advice of everyone around him. The ugly Princess Bâhbâh purses her mouth, presses herself upon him again and again, until the deaf servant takes pity on her, kisses her and rides off with her.

Finally Tino approaches on a white cow, beautifully dressed, accompanied by Hassan and her faithful playmates. Enraptured by the great beauty of the princess, the bull-headed one moves about on the throne with frightful, comical gestures. Tino is shown all the gold and precious stones in the sacks, and she brings herself to kiss the bull’s head on the mouth out of love for Hassan. Great darkness again, lightning, grimaces by firelight. When the dawn breaks again, Plumm Pasha has his former bearded head again and, as well as rewarding the princess with treasures, he elevates her to sit beside him on his throne – and hands her his large ruby heart. But Tino cries bitterly for she loves Hassan, who gestures for her to remain silent. But one of the people rushes to the Pasha and reveals to him that his redemptress loves Hassan, the son of the calipha Diwagâtme. The Grand Vizier now sends for the raiments of battle and a spear and sends the surprised youth to war.

But the moon rises gigantic in the sky, and the princess pretends to be tired, to fall asleep ... and beside her the Grand Vizier sleeps, along with all the people. And when the princess hears that all are fast asleep, she opens her eyes; the god Ptah has brought a jester. He exchanges clothes with the princess so that she can make her lucky escape. The Grand Vizier awakens, sees the jester next to him; the jester keeps nodding to him, and Plumm Pasha believes it to have all been a dream. So he hosts a great feast at which Tino and Hassan are married. Roses, water displays. Finally the god Ptah comes and blesses the two: Hassan and Tino.

‘Plumm Pasha’ by Else Lasker-Schüler was first published in German as ‘Plumm-Pascha’ in Das Kinobuch (ed. Kurt Pinthus), by Kurt Wolff Verlag in Leipzig, 1913 (copyright 1914).

This translation © 2020 James J. Conway