As we publish Three Prose Works today, here we look at the people to whom author Else Lasker-Schüler dedicated the constituent parts, a diverse range of figures who offer an intriguing insight into the writer’s life and interests. Lasker-Schüler was an intensely social individual, building up extensive networks of friends and associates, and as well as honouring them with dedications of books, poems and individual stories, she often wove them into her work as thinly fictionalised versions of themselves, or wrote short essays about them.

The Peter Hille Book

Peter Hille

Although he isn’t strictly speaking a dedicatee, from the title of the work itself to the 47 constituent sketches, with the majority bearing titles featuring the name ‘Petrus’, Else Lasker-Schüler’s first book of prose is wholly devoted to her mentor – the arch-bohemian writer Peter Hille (1854-1904). Hille issued just three novels and a play in his lifetime; he has never been translated into English and remains a reasonably obscure figure even in Germany. The gaunt, weather-beaten Hille would either doss with indulgent friends or simply camp out in parks and he aroused concern even among the chronically impoverished artists and writers of late 19th-century Berlin. Lasker-Schüler met Hille around 1899 and became his protégé. After she left her first husband, she and Hille greeted the new century as Berlin’s most notorious bohemians. This was the time when cabaret was introduced to the city, and the pair were there at the very beginning. In 1902 Hille opened a cabaret under his own name in an Italian restaurant popular with bohemians at the time; he was heading home from the venue one evening in 1904 when he collapsed and died. Two years later Lasker-Schüler issued The Peter Hille Book, its cover featuring a portrait of its subject which had adorned the wall of his cabaret.

The cover of Else Lasker-Schüler’s The Peter Hille Book (1906)

The Nights of Tino of Baghdad

Jeanette Schüler

The first edition of The Nights of Tino of Baghdad (1907) is dedicated to Lasker-Schüler’s mother, (‘To my mother the queen with the golden wings in reverence’). The writer was extremely close to Jeanette Schüler (1838-1890), and her earliest encounters with literature are bound up with their relationship; the young Else would act out the story of Joseph and his brothers for her. She was probably the most frequent dedicatee, sometimes together with the writer’s father (Aron Schüler), but more often alone. Jeanette Schüler died when Else Lasker-Schüler was 21, and for the rest of her life she almost always referred to her as ‘my dear mother’.

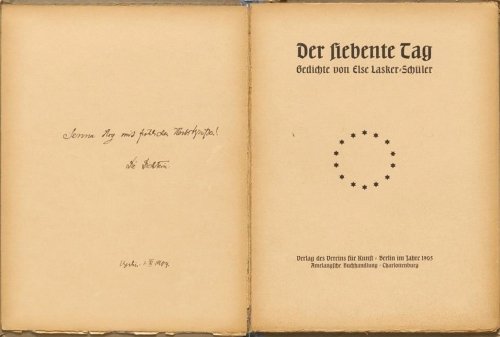

Senna Hoy

The second edition of The Nights of Tino of Baghdad appeared in 1919, and it carried a dedication to ‘my beloved playmate, Sascha (Senna Hoy)’. He also appears in the text as ‘Senna Pasha’. Senna Hoy was a name that Johannes Holzmann (1882-1914) adopted as a nom de plume at Lasker-Schüler’s suggestion, a phonetic reversal of his first name. A Jewish anarchist writer and bohemian, he published the journal Kampf! which frequently attracted the displeasure of the authorities. He was particularly inspired by the revolutionary upheavals in Russia in 1905, and two years later, just as the first edition of Tino went to press in 1907, Senna Hoy fled to the Russian Empire. By the time the second edition appeared, Senna Hoy had died of tuberculosis in a Russian asylum, despite Lasker-Schüler’s desperate efforts to free him. His body was brought back to Berlin and he is buried in the vast Weißensee Jewish cemetery. Lasker-Schüler was devastated; ‘Every shovelful of earth that they cast over his coffin, they cast over me’ she reported in a letter to Karl Kraus (a later dedicatee). You can read a little more about Senna Hoy here.

A copy of Else Lasker-Schüler’s second book of verse, Der siebente Tag (The Seventh Day, 1905), with a dedication to Senna Hoy

The Prince of Thebes

In contrast to The Nights of Tino of Baghdad, almost all of the eleven constituent tales of The Prince of Thebes – originally published in 1914 – were dedicated to various figures in the writer’s life. Conversely, it contained fewer characters from Lasker-Schüler’s life encrypted in the work itself (and far fewer than The Peter Hille Book, which teems with the writer’s associates). Jeanette Schüler returns as a dedicatee in the first tale in The Prince of Thebes, ‘The Sheikh’ (‘for my dear mother’), while ‘The Fakir’ is dedicated to Senna Hoy.

Aron Schüler

The book as a whole is dedicated ‘To my father Mohamed Pasha and his grandson Pull’. ‘Mohamed Pasha’ was Aron Schüler (1825-1897), of whom Lasker-Schüler evidently carried some fond memories, although her closest parental bond was clearly with her mother. Aron Schüler was a banker, but Lasker-Schüler thought this too mundane a profession and told people that he was an architect, claiming to have inherited her artistic talent from him. Her recollections focus on his child-like, pranking nature, noting also that this play could take on an almost violent dimension.

Paul Lasker-Schüler

Else Lasker-Schüler’s son Paul (1899-1927) features in both The Peter Hille Book and The Nights of Tino of Baghdad (as ‘Pull’). Here he shares the book’s dedication with his grandfather he never knew, while he is the sole dedicatee of the bloodthirsty tale ‘Chandragupta’ (which in the first edition was dedicated to Auguste Ichenhäuser, of whom little is known except that she was a Jewish artist and writer based in Munich and murdered in Theresienstadt in 1943). Paul’s birth in 1899 was the catalyst for Else Lasker-Schüler’s separation from her first husband Berthold Lasker, who was not the boy’s father. Paul was a promising artist, and Lasker-Schüler also tried to get him into early films, a project which foundered after he made an ill-advised pass at Leni Riefenstahl. He fell ill in the mid-1920s and Else Lasker-Schüler put her career on hold to care for him; he died in 1927 aged just 28. He is buried in the Weißensee Jewish cemetery, a few metres from Senna Hoy.

Paul Lasker-Schüler’s profile sketch of his mother on the latter’s book Konzert (1932)

Franz and Mar(e)ia Marc

‘The Dervish’ carries a dedication to the Expressionist painter Franz Marc (1880-1916), a great friend of Lasker-Schüler, and his second wife Maria Marc (1876-1955), an artist who also exhibited with her husband’s ‘Blue Rider’ group (her name rendered for some reason as ‘Mareia’). Franz Marc also provided three colour illustrations to The Prince of Thebes to complement the author’s own monochrome drawings. The couple took Lasker-Schüler in after her divorce from Herwarth Walden, but she couldn’t take the quiet of their country home. Later she was greatly shaken by Franz Marc’s death at the Battle of Verdun in 1916, and her 1919 work Der Malik, which picked up on the ‘Abigail’ cycle, took the form of ‘letters’ to the artist.

One of Franz Marc’s watercolour images for the first edition of The Prince of Thebes (1914)

Kete Parsenow

An actress who worked under directors like Max Reinhardt, Katharina (Kete) Parsenow (1880-1960) was sufficiently special to Lasker-Schüler to warrant two dedications in The Prince of Thebes. The first of the three main ‘Abigail’ tales is dedicated to the ‘Venus’ Kete Parsenow, while the brief appendage ‘An Incident from the Life of Abigail the Lover’, carries the unusual and specific dedication to ‘the Venus child Kete Parsenow when she was five years old’. The highly attractive Parsenow made a great impact on the avant-garde of Vienna when she performed there in the early 20th century, and was closely associated with two other dedicatees in The Prince of Thebes.

A recent edition of Kete Parsenow’s correspondence with Karl Kraus

Karl Kraus

The dedicatee of ‘Abigail the Second’, writer Karl Kraus (1874-1936) was an admirer of Kete Parsenow, and maintained a long correspondence with her, as well as with Else Lasker-Schüler, particularly in the period leading up to the First World War when she poured her heart out to him over pages. It is perhaps this confessional role that prompted Lasker-Schüler to refer to him as ‘The Cardinal’. Kraus is well known as one of the leading figures of the ‘Young Vienna’ group, alongside Arthur Schnitzler, Peter Altenberg and Hermann Bahr. A combative critic, he issued his own journal Die Fackel from 1899 until shortly before his death in 1936.

A volume of Else Lasker-Schüler’s letters to Karl Kraus

Walter Otto

The dedication of ‘Abigail the Third’ to ‘Walter Otto, the great youth’ introduces a figure who stands out as an anomaly among the predominantly bohemian, literary and artistic recipients of Lasker-Schüler’s acknowledgements. Walter Otto (1878-1941) was an academic – a historian and philologist focussed on antiquity, and a political reactionary who was active in (opposition to) the Räterepublik in Bavaria shortly after the First World War. More pertinently, from Else Lasker-Schüler’s perspective, he was the second husband of Kete Parsenow.

Erik-Ernst and Erna Schwabach

‘Singa, the Mother of the Dead Third Melech’ is dedicated to Erik-Ernst Schwabach (1891-1938), the co-owner of the publishing house which issued The Prince of Thebes, and his wife (Erna). Schwabach came from a rich Jewish banking dynasty, although he had little interest in the family business and instead took up writing, served as a patron to artists and writers, and established the ‘Verlag der weißen Bücher’ (‘White Book Press’) shortly before the First World War, focusing on works by Expressionist writers. Losing much of his inherited wealth in the hyperinflation of the 1920s, he died in exile in London in 1938.

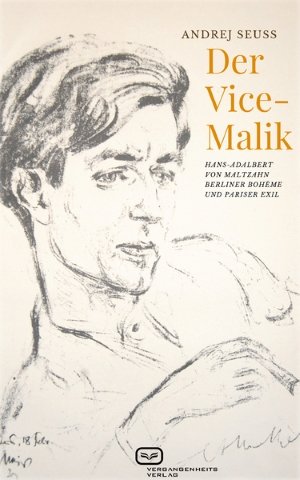

Hans Adalbert von Maltzahn

The tumultuous last tale in The Prince of Thebes, ‘The Crusader’, carries a dedication to Hans Adalbert von Maltzahn (1894-1934), a relatively obscure figure rarely evoked beyond the context of his association with Lasker-Schüler. Maltzahn came from an aristocratic background but as a young man made an impression on Berlin’s early 20th-century bohemian circles with his good looks and left-wing views. Lasker-Schüler was not immune to his charm, referring to him as the ‘Duke of Leipzig’ and along with this dedication wrote a number of love poems to him, although Maltzahn was evidently gay. Later she managed to get him out of active duty in the First World War through the intercession of Dadaist Wieland Herzfelde. As a forthcoming German-language biography details, Maltzahn worked as a theatre critic and translator and (after a trip to Brazil, from which he was expelled) moved to Paris in the late 1920s, where he died in 1934.

Three Prose Works by Else Lasker-Schüler (translated by James J. Conway)