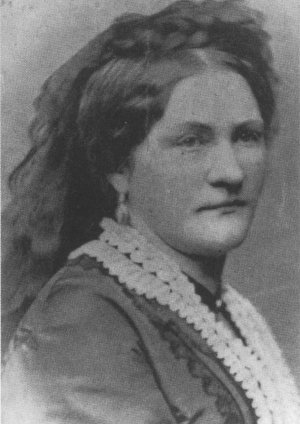

A cache of correspondence from Else Lasker-Schüler is up for auction in Berlin next week. Held in Croatia for many years, the collection includes postcards and letters that Lasker-Schüler sent between 1917 and 1920 to the art dealer and publisher Paul Cassirer and his wife, actress Tilla Durieux.

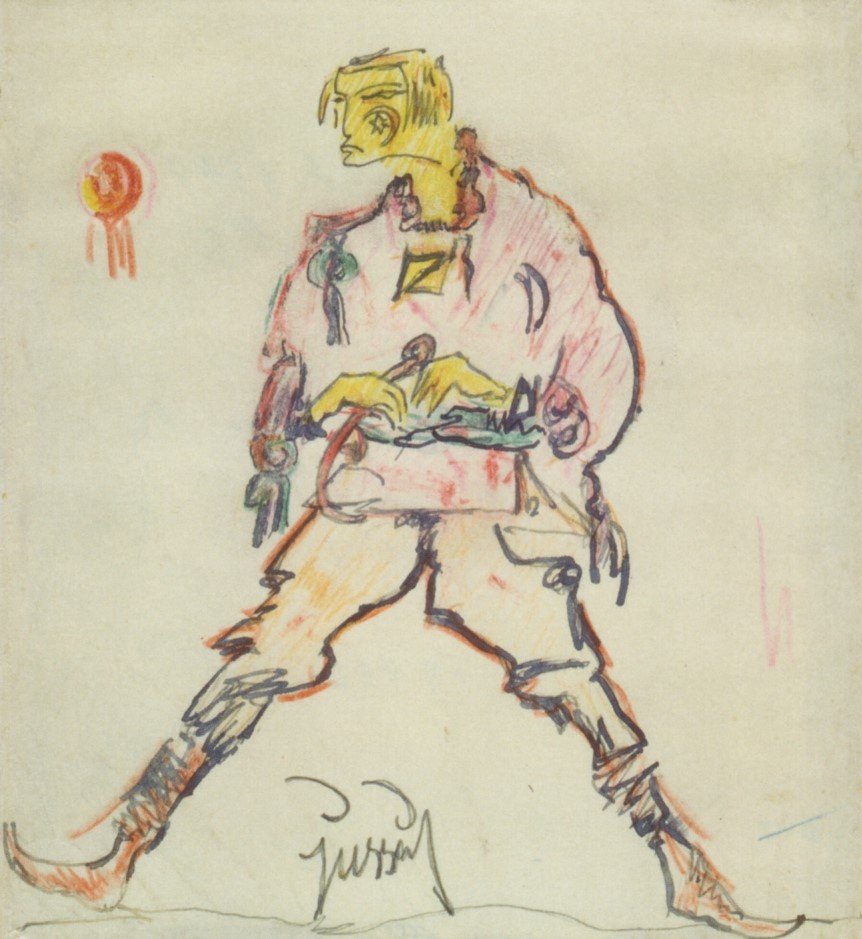

Paul Cassirer by Max Beckmann (1915)

Cassirer was a major catalyst of avant-garde art in Germany, promoting the work of Post-Impressionists, Secessionists and Expressionists from his Berlin gallery on a site where the Musical Instrument Museum now stands. Durieux was an acclaimed stage and early screen actress, and a subject of studies by Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Franz von Stuck. She had clearly warmed to her pen pal since her dismissive comment on seeing Lasker-Schüler with her son Paul and husband Herwarth Walden in Berlin’s Café des Westens in the early years of the 20th century (‘the little family lived, I suspect, on nothing but coffee’).

Tilla Durieux as Circe by Franz von Stuck, c. 1913

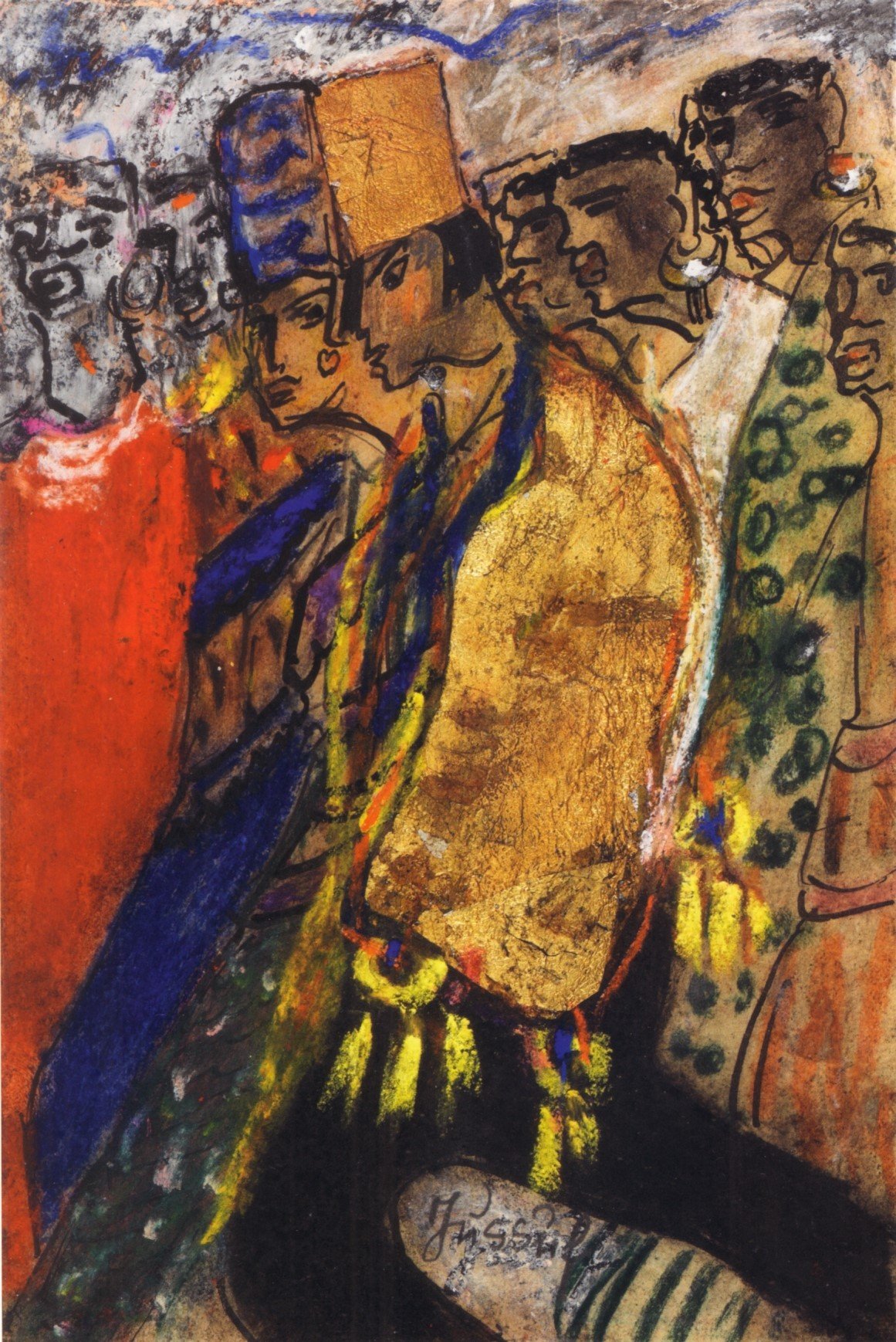

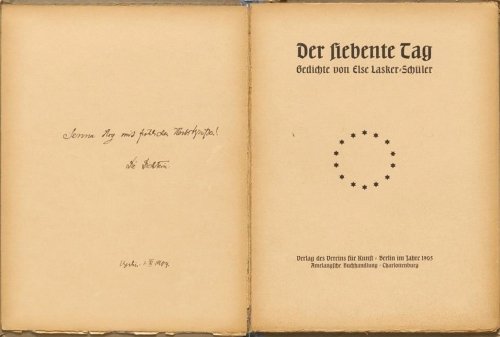

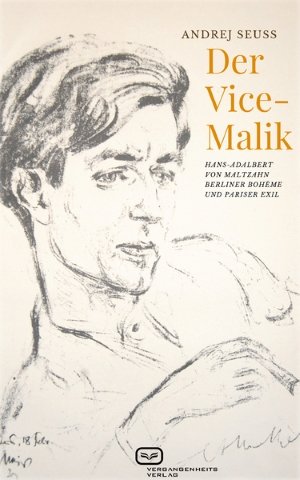

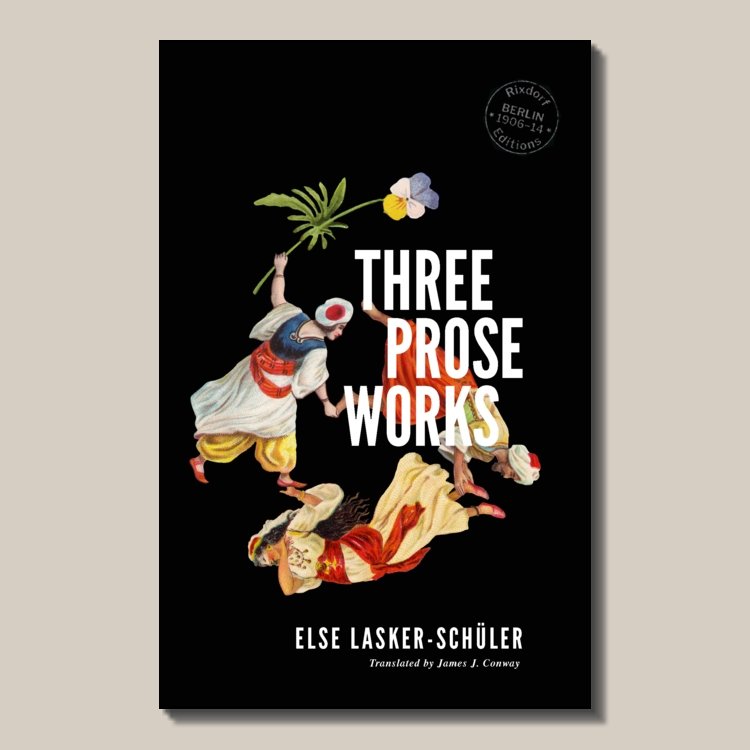

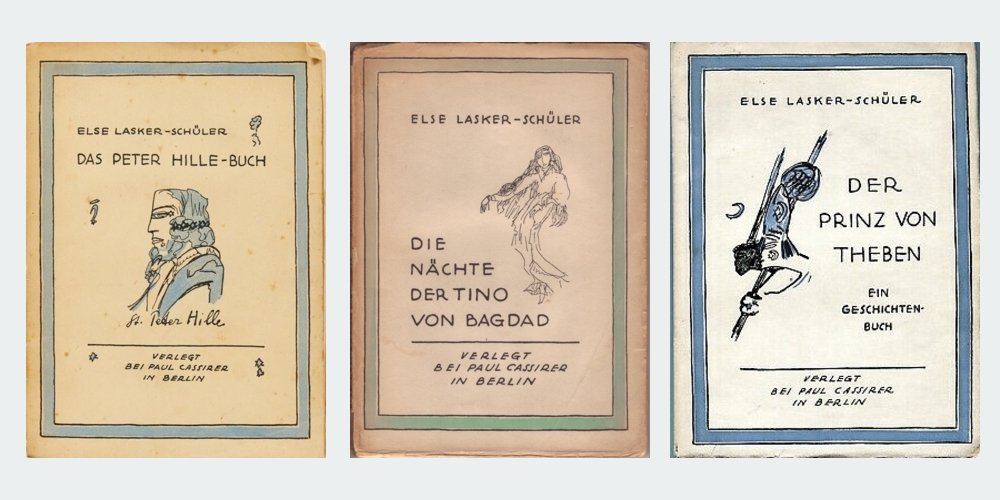

This hoard follows a similar find from 2020, the recipient in that case being a Dutch school teacher and part-time reviewer who corresponded with Lasker-Schüler between 1905 and 1930. Here we have a narrower time frame (1917-1920) but this, intriguingly, is the period in which Cassirer published a 10-volume edition of Lasker-Schüler’s works (including the trio that make up our edition, Three Prose Works). Else Lasker-Schüler invested a great deal of creative energy in her correspondence. Never a mere listing of events or airing of opinions, her letters – often embellished with drawings – served to expand the world she created in her verse, fiction, drama and graphic works, a construct into which she would implicitly or explicitly draw the recipient. Here she lavishes compliments on the couple, often in the guise of one of her alternative personae (‘I, the Emperor of Thebes …’), alongside images of another alter ego ‘Prince Jussuf’ with a crescent moon and six-pointed star on his cheek.

Lasker-Schüler later turned on Cassirer, referring to him as a ‘shark’ in her 1925 pamphlet, Ich räume auf! (Putting Things Straight) – a rogues’ gallery of publishers she felt had exploited and mistreated her. Shortly after publication, Cassirer and Durieux entered divorce proceedings; unable to face life without his wife, Cassirer committed suicide. Lasker-Schüler appears to have regretted her harsh words, and pencilled a note on a copy of Ich räume auf! that describes Cassirer as a ‘gentleman’ (using the English word).

The estimate is EUR 25,000; hopefully the lucky buyer will share the work with the public at some point.